Why Torture...

In the last

several years Western civilizations have

found themselves in the midst of more catastrophes than they could ever, in their

worst nightmares, have dreamed of. They could never have envisaged that the

history of the new century would encompass the destruction and distortion of

fundamental Anglo-American legal and political constitutional principles in

place since the 17th century.

Habeas

corpus has been abandoned for the outcasts of the new order in both the US and

the UK, secret courts have been created to hear secret evidence, guilt has been

inferred by association, torture and rendition nakedly justified

(in the UK the government's lawyers continue to argue positively for the right

to use the product of both) and vital international conventions consolidated in

the aftermath of the Second World War - the Geneva Convention, the Refugee

Convention, the Torture Convention - have been deliberately avoided or ignored.

It is the

bitterest of ironies that John Lilburne, the most important organizer of the

rights people in the UK and the United States claim and on which all

respective constitutions, written and unwritten, were built, achieved this in

large part as a consequence of his having been himself subjected to torture, to

accusations based on secret evidence and heard by a secret court, to being

shackled and held in extremes of isolation which exposed him nevertheless to

public humiliation and condemnation.

The worst

excesses of the last ten years, which destroyed the certainties of those

hard-won rights, should have sounded loud alarms, not least because of that

precise historical parallel; one key in attempting to hang on to legal and

moral concepts under attack is to remember their origin.

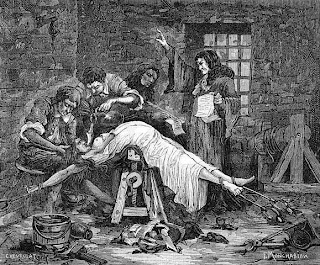

Lilburne,

an intractable young Puritan, with a strong sense of his rights as a freeborn

Englishman and a smattering of law, in 1637 was summoned before the Court of

Star Chamber - a court comprising nothing more than a small committee of the

Privy Council, without a jury, empowered to investigate. Lilburne had recently

been in Holland and was charged, o n the basis of information from an

informant, with sending loosely defined "fatuous and scandalous"

religious books to England. His defence was straightforward: “I am clear I have

sent none.” Thereafter he refused to answer questions based on allegations kept

secret from him as to his association with others suspected of involvement in

the sending of the books: “I think by the law of the land that I may stand upon

my just defence, and that my accusers ought to be brought face to face to

justify what they accuse me of.” For his refusal, he was fined 500 pounds, a

fortune for an apprentice, and was lashed to a cart and whipped thought the

streets of London from Fleet to Westminster.

Lilburne

was locked in a pillory in an unbearable posture (in today’s terminology a

“stress position”), but yet exhorted all who would listen to resist the tyranny

of the bishops, repeating biblical texts to the crowd applicable to the wrongs

done to him and their rights. On being required to incriminate himself: “No man

should be compelled to be his own executioner.” He survived two and a half

years in Fleet prison, gagged and kept in solitary confinement, shackled and

starving. The first act of the Long Parliament in November 1642 was to set him

free, to abolish the Court of Star Chamber and to adopt a resolution that its

sentence was “illegal and against the liberty of the subject, and also bloody,

cruel, wicked, barbarous and tyrannical.”

Lilburne’s

principled and public stance and the extraordinary political movement of which

he was part, the Levellers, produced far more than a brief reaction of

abhorrence to the use of torture and arbitrary imprisonment. By the end of the

17th century, there had crystallized the foundation of the concepts upon which

we draw now, most importantly the concept of inalienable rights that pertain to

the individual and not to the state. The Levellers insisted that the

inalienable rights were possessed by the people and were conferred on them not

by Parliament, but by God; no justification by the state could therefore ever

justify their violation. For the preservation of these and the limitation of

parliamentary power, the Levellers formulated a written constitution; never

adopted in England, in the new world it became a political reality. In both

countries, due process – the legal concept that gives effect to the idea of

fairness – was born from these ideas.

Once

evidence of any country’s willingness to resort to torture is exposed,

reactions of decency and humanity can be invoked without the necessity of legal

explanation. Less likely is any instinctive reaction to evidence in the

destruction of concepts of procedural fairness. Yet, in the imprecision and

breadth of accusations, leading in turn to the banning of books and the

criminalization of ideas and religious thought, and in the wrong committed by

secret courts hearing secret evidence, the lessons of John Lilburne and Star

Chamber have been in the last ten years deliberately abandoned and sustained

battles have still to be fought to reclaim the majority

The

shocking, reckless and ruthless disregard of all of these concepts seen in

recent years is neither new nor unique to the UK or to the US. The

history of regions other than Europe & North America, shows how fragile are

the laws and their applications that we assume protect us when faced with a

government determined to follow a contrary path. Repeatedly, historically, even

nations which have recently emerged from the fires of hell remember the

experience as it relates to themselves, but yet consign others to the same

fate.

Fewer than

ten years after then end of WWII, and only eight years from the UN Declaration

of Human Rights, the first reports of the use of torture by the French against

the Algerians fighting their war of independence began to emerge, with

justifications that today appear very familiar. The first official reports in

1955 admitted some violence had been done to prisoners suspected of being

connected to the FLN, but that this was “not quite torture”; “The water and the

electricity methods, provided they are properly used, are said to produce a

shock which is more psychological than physical and therefore do not constitute

excessive cruelty.”

Sartre

articulated the shock of realizing that torture had reappeared and was being

justified so soon after it had been categorized as an aberration found only

among psychotic and degenerate governments willing to violate all universally

understood and recognized principles of justice: “In 1943 in the Rue Lauriston,

Frenchmen were screaming in agony and pain; all France could hear them. In

those days the outcome of the war was uncertain and they did not want to think

about the future. Only one thing seemed impossible in any circumstances: that

one day men should be made to scream by those acting in their/our name.”

Written by Gareth

Peirce, a British lawyer who represents individuals who have been the subject

of rendition and torture

Comments